Preface: The proceeding is my final analysis of the Race, and it’s more of an essay than a blog. I have tried to encapsulate the last eleven months of my life into a piece of writing that not only can hopefully put into words what I intangibly feel within me for your understanding, but also for me to look back on in the future when I ask myself the question, “How was the trip?” While it may appear to be more literature in nature at points, I assure you that the comparisons and analysis seem to me not only necessary but also more adequate than any of the blogs previously composed on their own merit. As a final precaution, I feel as though I’m attempting the unattainable. Mothers, how do you put into words the experience and feelings of childbirth? You make comparisons that inevitably fall short.

Preface: The proceeding is my final analysis of the Race, and it’s more of an essay than a blog. I have tried to encapsulate the last eleven months of my life into a piece of writing that not only can hopefully put into words what I intangibly feel within me for your understanding, but also for me to look back on in the future when I ask myself the question, “How was the trip?” While it may appear to be more literature in nature at points, I assure you that the comparisons and analysis seem to me not only necessary but also more adequate than any of the blogs previously composed on their own merit. As a final precaution, I feel as though I’m attempting the unattainable. Mothers, how do you put into words the experience and feelings of childbirth? You make comparisons that inevitably fall short.

During my final days of ministry, I began reading the book Gulliver’s Travels, which is far more than a children’s tale of adventure. Specifically it’s a satire of English society centuries ago, but in general it’s a critique of different perspectives and allows for creative comparisons to whatever the reader categorizes as “home.” After finishing this book the day before I departed for Final Debrief, I knew it was the key to explaining this year abroad, after serving in cultures foreign compared to my normal, yet normal to those I see as foreign. For said reason, I am going to briefly summarize the classic adventures of Gulliver before entering into explanations of the story’s applicability to my Race.

Gulliver’s Travels is divided into sections based upon the four countries that Gulliver became stranded upon. Each world was not intended to be merely an entertaining exploit, but a creation that brought to life quite normal human perspectives.

First, Gulliver enters the land of the Lilliputans who are mere hundredths his size. He is able to instill fear into criminals by feigning hunger, quench a raging fire with his urine, and seize an entire navy with his bare hands. In this land, nearly everything about Gulliver is superior. His perspective is the highest, and therefore the greatest, in the land.

In his second journey, the roles are entirely reversed. Gulliver is literally the same height as grass, and the natives are proportional to the landscape. In this country he is first put on display as a novelty for money, until he is purchased by the Queen. While he had intellect, agility, navigational skills, and musical gifting, nothing he did could earn the respect of his superiors. While nothing had changed about him physically, due to his abnormally large surroundings he was humbled in every sense of the word. Really, how important could the perspective and counsel be of someone who was nearly killed by rats, bees, a falling apple, and was carried away by a bird?

On his third voyage, Gulliver ends up in a country that has a floating island hovering above it. These people literally had their heads in the clouds, cared for little outside of mathematical and musical theory, and had to be struck in the face in order to take their attention off of themselves. While on this land, the author evaluates ancient, modern, and post-modern history coming to the unsaid conclusion that elitist advancement is pulling down society and its morals in the name of progress.

On his third voyage, Gulliver ends up in a country that has a floating island hovering above it. These people literally had their heads in the clouds, cared for little outside of mathematical and musical theory, and had to be struck in the face in order to take their attention off of themselves. While on this land, the author evaluates ancient, modern, and post-modern history coming to the unsaid conclusion that elitist advancement is pulling down society and its morals in the name of progress.

Lastly, Gulliver is abandoned on a land where horses are the superior beings in strength, morals, and intellect. On the contrary, humans, called Yahoos, are the most inferior beings known to exist. Lying and opinions don’t exist here, for what is of the greatest rational reason is always done. After three years of living with the horses, Gulliver is appalled by all Yahoos, who are known for their pride, greed, and selfishness. He easily associates these beasts with the citizens of his nativeEngland who start wars, practice corruption, and look out for their own well-being. It’s in this faraway land that Gulliver feels as though he has gained a new perspective on life that he only could have gained by being removed from humanity, and he believes that any attempts to express such a perspective to his peers would be futile. The story ends with Gulliver having to return to England against his desires. He is unable to re-enter English society because of his new perspective of the human race. Only after five years at home does he even allow his wife to sit on the far end of the dinner table with him.

their pride, greed, and selfishness. He easily associates these beasts with the citizens of his nativeEngland who start wars, practice corruption, and look out for their own well-being. It’s in this faraway land that Gulliver feels as though he has gained a new perspective on life that he only could have gained by being removed from humanity, and he believes that any attempts to express such a perspective to his peers would be futile. The story ends with Gulliver having to return to England against his desires. He is unable to re-enter English society because of his new perspective of the human race. Only after five years at home does he even allow his wife to sit on the far end of the dinner table with him.

In the afterword, the fictional author goes on to explain that the preceding account can’t be argued with for it is his story. It is his testimony of what happened to him, as unbelievable it may appear to be. What Gulliver experienced was life outside of the bubble he knew to be human existence, beyond his own world, beyond what people would believe, beyond what even his own mind would at one point have told him was true. Every place he visited was different, but he was always himself in every way. Nothing changed about him externally, merely—yet also more significantly—internal shifts were made.

In the afterword, the fictional author goes on to explain that the preceding account can’t be argued with for it is his story. It is his testimony of what happened to him, as unbelievable it may appear to be. What Gulliver experienced was life outside of the bubble he knew to be human existence, beyond his own world, beyond what people would believe, beyond what even his own mind would at one point have told him was true. Every place he visited was different, but he was always himself in every way. Nothing changed about him externally, merely—yet also more significantly—internal shifts were made.

I’ve realized throughout this Race that as compelling as books, such as Gulliver’s Travels, are they are nothing more than someone else’s stories. They lived it; I only read it. Throughout the World Race I was an author, not just literally by writing blogs, but figuratively as well. I didn’t just read about faith, hope, love, community, covenant, sacrifice, and surrender, but I lived it. The World Race is my story, my testimony. Keeping in mind the four adventures of Gulliver, I humbly recount for you Weston’s Travels.

I entered this Race with a subconscious belief of my superiority. I actually believed that I could changethings. Entering into Central America, where the people didn’t speak my language nor did they have financial backing or education to change that, I somehow fell to the thought that the American way is the better way in every way. We have good tools, clean water, education, etc. Here, I had something to offer. Here, I served with the first true man of faith I’ve ever gotten the privilege to know. He told his story selflessly and humbly, yet confidently. It was his story whether or not my upbringing valued or even conceded to the influence of demons and current usage of the spiritual gifts. Here, I wrestled with a question in my thoughts and felt, in an unexplainable way, the answer of “grace,” when I angrily asked God, “Why me?”

I entered this Race with a subconscious belief of my superiority. I actually believed that I could changethings. Entering into Central America, where the people didn’t speak my language nor did they have financial backing or education to change that, I somehow fell to the thought that the American way is the better way in every way. We have good tools, clean water, education, etc. Here, I had something to offer. Here, I served with the first true man of faith I’ve ever gotten the privilege to know. He told his story selflessly and humbly, yet confidently. It was his story whether or not my upbringing valued or even conceded to the influence of demons and current usage of the spiritual gifts. Here, I wrestled with a question in my thoughts and felt, in an unexplainable way, the answer of “grace,” when I angrily asked God, “Why me?”

Entering Asia was like entering a world surprisingly foreign. The language was undecipherable and, therefore, unpronounceable. The population was virtually entirely Buddhist with a 2% Christian flicker that burned hot. Here, more than anywhere else, they asked questions about America beyond the surface topics of music, food, and fun. My answers were generic, inadequate, and stale. Here was a culture that valued the head both for its intellectual function and saw it as the most sacred part of the body. Here, I saw a man weep over the thought of grace. Here, I heard about current and targeted genocide that previously to me had been unknown, unheard of, and unbelievable. Here I saw that the church was not just an Americanism. What I did here was the most humbling. I cut trees, played soccer, and entertained kids.

Entering Asia was like entering a world surprisingly foreign. The language was undecipherable and, therefore, unpronounceable. The population was virtually entirely Buddhist with a 2% Christian flicker that burned hot. Here, more than anywhere else, they asked questions about America beyond the surface topics of music, food, and fun. My answers were generic, inadequate, and stale. Here was a culture that valued the head both for its intellectual function and saw it as the most sacred part of the body. Here, I saw a man weep over the thought of grace. Here, I heard about current and targeted genocide that previously to me had been unknown, unheard of, and unbelievable. Here I saw that the church was not just an Americanism. What I did here was the most humbling. I cut trees, played soccer, and entertained kids.

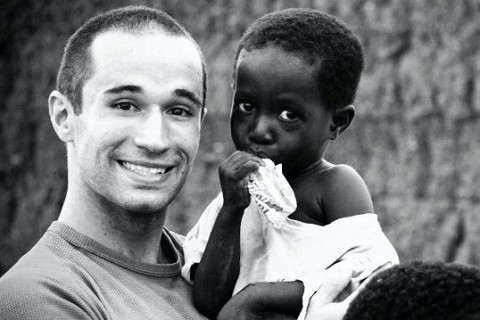

While in Africa I failed to describe the continent in my blogs due to the lack of comparisons. (What other city does one compare Venice to?) It seemed as though everything there was louder, dirtier, and prouder. The land more populated, the people more in your face, and the Christianity more obvious. As missionaries we flew in with our tattoos, bracelets, and mohawks into a conservative culture that has stigmatized all those accessories. Here, American churches would be put to shame in terms of the worship, the prayer, and the passion of the congregation. Simultaneously, though, I saw things that were wrong, that were inappropriate, and that were witchcraft. I saw truth twisted and prosperity idolized, yet I left this continent humbled. Although nothing about me physically had changed, I felt small, but not in a bad way. Oddly enough, small seemed like just the right size.

Finally, some of my time in Eastern European villages actually kept coming to mind as I was reading the fourth part of Gulliver’s Travels. Here, families lived together and communities knew and helped their neighbors. The villagers were self-sufficient and pursued God by dedicating their whole life—not just part—to God’s service. Here, I realized that I had less and less to say as the Race went on, let alone the ability to change things on my own strength. Even some of the tasks I helped with, digging and preaching, they could either do better than me or I at least needed their help. Here, I saw simplicity reign over the complexities and materialism of the West. Here, I read Gulliver’s Travels and I have to wonder if reading this book during this one particular week in my life was coincidence? But now when I wonder, I lean more towards belief than amiable speculation.

As I return home, I do not intend, nor desire, to isolate myself from the Yahoos. While possibly an over-the-top finish, Gulliver’s reaction to normal life isn’t such a stretch. It’s comparable to anyone who knows that this world is not our home. That a greater place of rest, rejoicing, and restoration remains in waiting for us.  While Gulliver’s return was done in despair and disgust, I desire to return with a banner of hope, love, and faith, for while the paths of me and our famous sailor oftentimes converged throughout our journeys, this is where we diverge and I divulge the point of this post.

While Gulliver’s return was done in despair and disgust, I desire to return with a banner of hope, love, and faith, for while the paths of me and our famous sailor oftentimes converged throughout our journeys, this is where we diverge and I divulge the point of this post.

Unlike Gulliver, throughout this whole year, I had the opportunity to live in a wall-less church whose only limit was itself. Denominational protocols were absent, decisions were made based on the Spirit’s leading, corrections were dealt with in love, and members were encouraged and built up. It’s a church that you don’t want to leave out of reluctance that a comparable one wouldn’t be found. That leaving would cause you to be alone, not physically, but emotionally unable to be surrounded by others who would understand what you’ve been through. That leaving would mean you’d have to figure out how to explain the perspective that you are chasing, pursuing, with the hope of one day grasping.

There are more cultures to explore and experience, as there are more perspectives to acquire. But no matter the length or zeal of the chase, in the end I’m limited.  I can go around the world over and over again, discover and experience new cultures and revelations, but I’ll always be a Yahoo–in human eyes. In human eyes, I’ll be a wretch, a sinner, and an imperfection, but that’s not how God sees me. In all the lands in all the worlds that I could be stranded on, one perspective remains superior to all. Because of Jesus’ sacrifice, God sees me as righteous. Because of grace, I have authority, walk in freedom, and am loved. Therein lies the remainder of my Race. My pursuit is to shift my perspective to see myself, and others, as God sees us: children that He loves.

I can go around the world over and over again, discover and experience new cultures and revelations, but I’ll always be a Yahoo–in human eyes. In human eyes, I’ll be a wretch, a sinner, and an imperfection, but that’s not how God sees me. In all the lands in all the worlds that I could be stranded on, one perspective remains superior to all. Because of Jesus’ sacrifice, God sees me as righteous. Because of grace, I have authority, walk in freedom, and am loved. Therein lies the remainder of my Race. My pursuit is to shift my perspective to see myself, and others, as God sees us: children that He loves.

Sounds pretty simple and cliché when you read it, huh? I humbly ask, though, that you remember that I wrote it. It’s my story, and, after all, it did take me eleven months to write.