hour of crazy traffic to Atlanta to see a movie. Not just any movie. In

fact, the length of the film qualifies it more as an episode of your

favorite sitcom. Your favorite half-hour sitcom, at that.

Interesting, you might say. Why would dozens of missionaries risk their lives on the unpredictable crash-course which is downtown Atlanta?

Risk our lives we did, at least those of us in the gray van (I’d like

to pretend I’m joking), but we arrived at the Fox Theatre right at showtime. 7pm. Fortunately, so many people were busy pouring into

the theatre that they didn’t even get started until a full twenty minutes after that.

I’d never been to a movie theatre this big

(granted, I’m from a small Mississippi Delta town and four screens at a

mom-and-pop theatre is that to which I am accustomed). It was insane.

Floods of people surrounded me. I couldn’t even guess how many, but at

the end of the night, I’d learn that there were more than 4,500 people in attendance for

this film.

As you’ve probably

guessed by now, this was no ordinary occasion. I guessed that by the

podium chillin’ on stage to the right of the screen. Someone walked up to it. They

talked. They spoke about an issue that many of the crowd had probably

never even heard about before or even knew existed. They detailed events

and statistics that, to my humble hypothesis, probably very few people

even grasped and even fewer had seen.

They spoke

of rape. Not the type of talk you’d expect to hear, but they spoke of

it. And as one of the speakers most clearly put it, “The rape of

children for profit.”

They spoke of child sex trafficking.

Surrounded by the scores of people who were awed at the statistics, the

virgin minds that were becoming aware of the issue in that very room at that very moment, the room was awash in audacious silence and shock.

But in my corner, I was surrounded by a group of people that not only knew about the issue…

We had seen it. We had fought against it. We had

walked the roads where it happened and entered the bars and businesses

where it occurred. We had held those who were victims. We had prayed

against the spiritual forces that enslaved these children of God in a

cycle of endless suffering. We had wept over the genocide of innocence

that left oceans of victims nothing more than hollow bodies, casualties

of life, animated merely by existence.

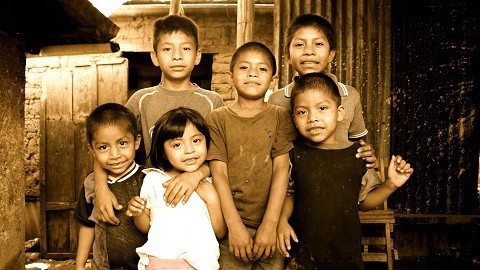

We knew their faces.

We knew their names.

We knew their stories.

Despite this, I still found the numbers overwhelming. The issue addressed primarily focused

on the issue of child sex trafficking in Atlanta, which is unbelievable

in itself. I couldn’t help but think of the children in the city who had been

purchased on that very day. According to one of the speakers, most

likely purchased on one of the roads we took to get to the theatre. Unbelievable.

As I watched The Candy Shop, which depicted a

depression-era fairy tale of a man who turns little children into candy for consumption,

I couldn’t help but find my mind elsewhere. As awesome as the movie was

(one of the coolest indie films I’ve seen in terms of appearance and atmosphere) I didn’t find myself as disturbed as I thought. To many, I’m sure

it was quite eerie, especially for those who were being exposed to the

issue for the first time.

see a face.

provide for their families. I see the girls on that road, nowhere near able to pass for adults, no one saying anything. I see those dressed

as children for the express purpose of eliciting a customer, normally

three or four times their age. In the moments it takes to introduce myself, I see tragedy in each painted smile, forced for culture’s sake. Forced for living’s sake.

I see the streets of Phnom Penh, the

biggest city in the world for child prostitution. I see the children

in the alleys and the streets. I see the statistics that say that more

than one-third of all sex workers in this city are children. I see the

ads on the back of tuk-tuks that beg foreigners not to harm

Khmer children. I see the old white man and the little Khmer boy riding

with him in that very same tuk-tuk. I feel the same nausea this second that I felt six months ago.

I taste the dust of Uganda. I smell the odor of

unwashed masses fervently listening to our preaching. I see the girls

that step forward, repeatedly having been raped during the war. I see

their tears. I hear their wails. I see them as they hit the dust and

weep for those years spent as sex slaves to the Lord’s Resistance Army.

Some weep for innocence lost more than twenty years ago, some weep for what was stolen weeks ago.

pain that hasn’t lost it’s razors. I think of their eyes, eyes that look

like holes. Pits that don’t seem to have a bottom, pits that seem

overflowing all the same. Gushing with a pain I can’t grasp, a violation

that never, ever ends.

I could say I’m a veteran. I’m an alumni of The

World Race. I’ve put in my time and I’ve done what I could. On this

night, I can look at the rows of the soldiers beside me, in front of me,

behind me. As they watch this film and listen to the speakers, I know

they’re not seeing and hearing Doug Jones or Brandon McCormick or Street Grace or Twelve Stones or Whitestone Pictures.

toddler sold by his parents into sex slavery. They are praying for the

little Thai girl on Bangla Road, sold to a man old enough to be older than even her grandfather. I am holding a Ugandan teenager in the dust, so much more falling away than the tears making red mud on the ground. The tears from both of us.

I could say I’m a veteran. But though I’m no

longer in these places, holding these hands and listening to these

voices, the war that I fought in still fights in me.

I’m

not a veteran of this war, and I won’t be until the last battle in this

war is over. Or until I see the complete redemption of all the victims before the throne of our Redeemer.

Whichever comes first.