Imagine you’re in your home when you get a knock on your door. “Excuse me, but I’m going to need you to evacuate this city immediately. It’s for your own safety. We’re concerned the United States may be targeting this area and we wouldn’t want you to be blown away by a bomb, now would we?” You’re taken aback and suddenly anxious about the whole situation. “Oh don’t worry. It’ll only be 2 or 3 days. You can even leave your house unlocked. The Khmer Rouge will take care of everything for you until you return. I assure you, it’s only 2 or 3 kilometers outside the city but please, hurry up. We musn’t waste anymore time.” What would be going through your mind right about now?

What if it didn’t happen that way? What if instead of giving answers, he merely pushed you around? What if instead of a peaceful tone, he screamed? What if he had a gun to your head throughout the whole process? What if you were one of the hundreds of thousands forced with this reality?

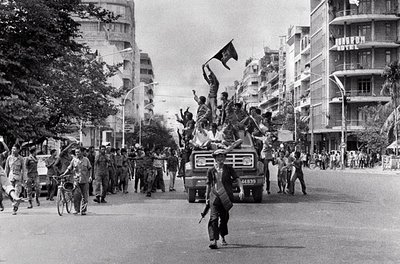

On April 17, 1975 life changed for the people of Phnom Penh. Amidst joyous celebration for an end to civil war, evil was brewing and they didn’t even know. Khmer Rouge entered the capital and the civilians rejoiced, unaware of what was to come. Unfortunately,  the troops were not there to celebrate with them. They soon ordered people to abandon their homes and leave Phnom Penh on foot, all the while having guns at their heads. By mid-afternoon, hundreds of thousands, estimates up to even 2 million, were on the move out of town to a far off countryside. Told they’d be gone for only “two or three days” and that they were merely going “two to three kilometers” away because of the “threat of American bombing,” these individuals no longer knew what to believe. As many as 20,000 died along the way. What they were walking for, they didn’t know. All they knew was to walk.

the troops were not there to celebrate with them. They soon ordered people to abandon their homes and leave Phnom Penh on foot, all the while having guns at their heads. By mid-afternoon, hundreds of thousands, estimates up to even 2 million, were on the move out of town to a far off countryside. Told they’d be gone for only “two or three days” and that they were merely going “two to three kilometers” away because of the “threat of American bombing,” these individuals no longer knew what to believe. As many as 20,000 died along the way. What they were walking for, they didn’t know. All they knew was to walk.

This evacuation was just one of many for the people of Cambodia. It became the norm for a nation falling under control of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. The goal of the Khmer Rouge, in short, was communism. This was not possible in cities, according to them, for cities were the breeding  ground of capitalism. In order to create the perfect communistic community, everyone would have to live in the countryside as peasants. Peasants were the ideal. They don’t rebel. They are uneducated. They are simple and hard-working. They are the ideal.

ground of capitalism. In order to create the perfect communistic community, everyone would have to live in the countryside as peasants. Peasants were the ideal. They don’t rebel. They are uneducated. They are simple and hard-working. They are the ideal.

The life ahead was not one of luxury either. Those that survived the trek soon found that their past life was history. All rules, all rights, all responsibilities previously held were thrown out the window. There were new rules here and one should not disobey. This was Year Zero. There was no more Cambodian history or family history for that matter. Families were torn apart and forced to denounce each other, and children were even used to betray their families. Young children were seen as pure and untainted by capitalism and family influence. Because of this, they were brainwashed into becoming spies and would report back their families’ activities.

previously held were thrown out the window. There were new rules here and one should not disobey. This was Year Zero. There was no more Cambodian history or family history for that matter. Families were torn apart and forced to denounce each other, and children were even used to betray their families. Young children were seen as pure and untainted by capitalism and family influence. Because of this, they were brainwashed into becoming spies and would report back their families’ activities.

The main goal here was to work. This was an area focused on agricultural success so you better be successful. That means, produce an average national yield of 3 metric tons of rice per hectare (1.4 tons per acre). Easy enough, right? Not when the average national yield was only one metric ton of rice per hectare pre Khmer Rouge days, let alone now with these “rules.”

Workdays in the fields started at 4 a.m. and ended at 10 p.m., with only two rest periods allowed in between, all under armed supervision of course. The slightest infraction would get you killed by the young soldiers, thirsting for blood. Workers were expected to live on one tin of rice (180 grams) per person every two days and were forbidden to eat the fruits and rice they were harvesting. Starving workers were simply told, “Whether you live or die is not of great significance,” as they slowly watched each other whittle away, eventually to death. The people who survived, but were not well enough to work, often vanished: after being taken to a distant field or forest, they would be forced to dig their own graves before the soldiers would bludgeon them on the back of the head with a shovel or hoe. It didn’t matter whether the victims died; either way, they were buried and left for dead.

Workdays in the fields started at 4 a.m. and ended at 10 p.m., with only two rest periods allowed in between, all under armed supervision of course. The slightest infraction would get you killed by the young soldiers, thirsting for blood. Workers were expected to live on one tin of rice (180 grams) per person every two days and were forbidden to eat the fruits and rice they were harvesting. Starving workers were simply told, “Whether you live or die is not of great significance,” as they slowly watched each other whittle away, eventually to death. The people who survived, but were not well enough to work, often vanished: after being taken to a distant field or forest, they would be forced to dig their own graves before the soldiers would bludgeon them on the back of the head with a shovel or hoe. It didn’t matter whether the victims died; either way, they were buried and left for dead.