Clay Warren Hunt. Marine, Scout Sniper, Purple Heart recipient. Big-hearted humanitarian, sheepish grin, always making new friends. He had a big tattoo on his forearm that said “Not all who wander are lost”… and it suited him perfectly. Clay was one of those guys that you just wanted to be friends with. His smile and laughter were contagious and his heart was driven to help and serve others. He was a son, a brother, and a best friend. Growing up, he loved to spend time on his grandfather’s farm in Texas, hunting and fishing. He was a Texas boy to his core and damn proud of it. He loved life, loved his family, and loved showing others that life had so much more to offer than they ever dreamed possible. He was so good at unlocking the mysteries of life that sometimes I wondered if he was hiding the keys around his neck, next to his HOG’s Tooth that he received after completing the Scout Sniper Basic Course. It was no surprise that he was so clever. His apartment was full of books on everything from philosophy to history to the classics and everything in between. Once while standing in his apartment, I asked why he had so many books that he never read… Boy, was I wrong. I got the Cliff Notes version on each of them and then some.

I met Clay in the way that any two good Marines meet each other… at a bar. I was living in Manhattan Beach at the time and I had a friend in town who I had served with in the Marines. He was now a Sergeant in the elite Force Reconnaissance Company, just back from a deployment to Afghanistan. Ben was one of my favorite junior Marines during my second deployment and we had trained together while he was preparing for Recon. I hadn’t seen him in quite a while, so it was nice to have the chance to catch up and have a few beers overlooking the Manhattan Beach pier. Anyone who’s ever been to MB knows Shellback tavern. It’s the perfect beach dive bar with surfboards on the ceiling, wooden surfboard tables, and even Pebble Beach golf arcade game and Pac-Man. So, we were sitting having a beer and catching up when this guy in an American flag baseball cap walks up to Ben and says “Hey, I know you.” Ben and I look at each other and just kind of stare blankly at the guy and Ben says “No, I don’t think so.” To which Clay replies “Yeah, I do. We went to School of Infantry together. Ben, right?” The funny thing about the Marine Corps is that it’s one big family and once you are brothers, you are brothers for life. So, as you can imagine, there were some hugs and some trading of war stories and a few more beers. Next thing I know, we’ve cleared off an entire table and Clay has invited some random strangers over and we’re playing “flip cup” with half the bar. If you’ve never played flip cup, you should probably Wikipedia that and gather some friends. We had a blast. Before we parted ways, Ben and I got Clay’s number. I had been living in MB for a while and had a hard time making any friends worth keeping so it was awesome to see there was a fellow jarhead down here by me.

Clay and I at a bar in Manhattan Beach, trouble as usual.

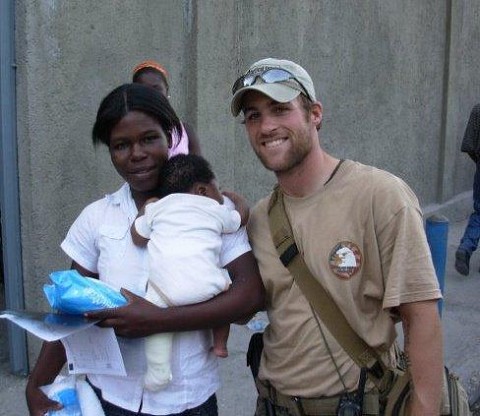

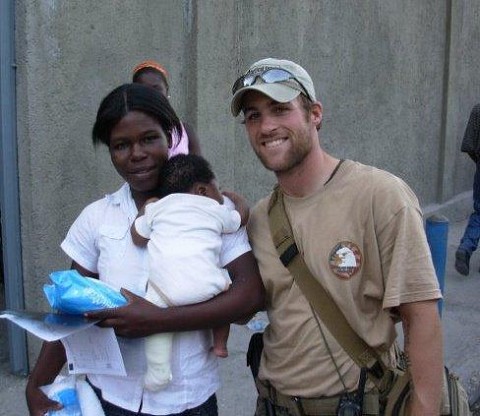

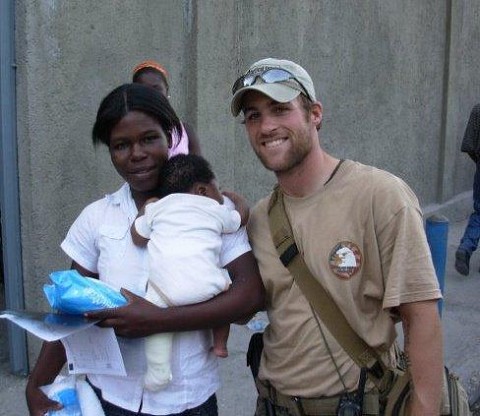

Before Clay left, he mentioned that he had just come back from the earthquake in Haiti with a few other veterans and a small team of doctors. His sniper partner, Jake, had seen the earthquake on TV and had somehow gathered a small team and chartered a flight to Port-au-Prince. They had spent the month saving lives, clearing rubble, and treating a wide variety of injuries and illness. They had decided to turn the group into an organization named “Team Rubicon”. Here were vets who had recently gotten out of the military and had continued to find a way to fulfill the sense of purpose that drives us military folk by helping others and conducting search and rescue following major natural disasters around the world. Now this was something right up my alley. I didn’t know it at the time but Clay had also been working with several other veterans’ organizations, speaking before members of Congress about veteran’s issues, and even appearing in a television ad that aimed at letting veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan know that they were not alone when they return home. Clay was always doing something to help others.

After we left the bar, I continued to keep in touch with Clay. A few friends and I were doing a Spartan Race mud run the next weekend and we were organizing a bunch of people to come camping with us the night before the race. So, Clay came out and we continued to hang out from there on. I had just gotten a new mountain bike for Christmas and it turns out that Clay also liked to ride. So, I loaded the bike into my truck and headed over to his apartment. When I got there, he looked at my $500 hardtail bike and said “You’re not riding that, are you?” He took me up to his living room where he had about 4 different mountain bikes and a road bike all standing on a nice bike rack, with parts and tools scattered about the floor. He pulled down a much nicer bike than I had, tuned it, pumped the tires, and said “Ok, ride this one.” I started to get the feeling that I was in for more than just riding up fire roads. We drove out to the Santa Monica mountains and Clay started heading up a steep path with stairs, so I did my best to keep up. We climbed for about 40 minutes before reaching a hilltop and I thought “Finally, we can relax a bit”. Nope. The hill made a sharp downward turn over a set of stairs and so I got off my bike and started to walk it down the side. Clay pulled up next to me and said “What the hell are you doing?” Then, he shot me a sheepish grin, backed up a bit, came to full speed, launched over the stairs, landed, and kept riding along up and over the next hill, doing the same again and again. I stood there and watched him fly around the turns and jump off the drops, kicking dust and dirt and rocks all over the place. And I smiled to myself in admiration and thought “it’s gonna be a looong day”.

That day, I lost count of how many times I wrecked or flew over my handlebars. On some of the downhills, I walked my bike every chance I thought I could when he wasn’t looking. This guy was trying to kill me. We went down the steepest, nastiest, rockiest trails I have ever seen, all the way down to the valleys. Then, we would climb up again all the way to the top of the mountains, screaming along the thin ridgelines as Clay would hit waist-high dirt jumps and get a solid 8 feet of air. I remember telling him I wished I had a camera to record him biking and he just replied “for what?” At one point, we were headed down a crazy steep mountainside of loose rock. I was trying to keep up with him so he didn’t have to keep stopping and waiting for me. I let go of my inhibitions and did what he did, going as fast as I could down the rocks. Then, my tire went sideways… and I hit the ground at a solid 25mph and skidded halfway down the hill. I layed there for a moment before getting up. I had taken all the skin off my right fore-arm and bent the handlebars so that they were facing sideways. I walked the bike down the hill and found Clay waiting for me. He saw me and said “Dude, what happened? I thought I was gonna have to come up there and get you.” I showed him the bike and my arm and he just laughed at me. He grabbed the bike, pulled some tool out of his backpack, fixed the handlebars so they were straight again and said “Ok. Let’s go.” By the end of the day, I was covered in blood, my shirt was ripped, and my legs were so cramped that I couldn’t pedal uphill anymore and whenever I got off the bike my legs would collapse underneath me. We finally made it back to the parking lot after about 4 hours. Clay looked at me and said “Well, you don’t quit. That’s for damn sure. I was just testing you to see if you have what it takes to be a member of Team Rubicon”. When my girlfriend saw the massive scrape on my arm later that day, she said “You’ve got a new best friend, don’t you?” Followed by what became her all too common phrase “Oh, you boys”. She was right; an epic bromance had begun.

Clay in Haiti with Team Rubicon after the earthquake, 2010

Clay and I were together every chance we got. Or, at least, every chance I got. He was really my only close friend in the area since I still had a hard time making friends who weren’t in the military. I worked the night shift near his house, so sometimes I’d bike all day and only get a couple hours of sleep before going back to work. The more we biked, the more Clay started to open up. He had a lot of rough experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan, many that reminded me of my own. We would bike and talk about war and life and dreams. It was during these times that I saw Clay at his most natural state, at ease, and at peace. When we weren’t biking, we spent plenty of time wreaking havoc on the bars and strip of Manhattan and Hermosa Beach. Sometimes we’d pick up a couple of 40’s and climb up the back side of the multi-million dollar beach homes that were being built along the strand. We’d climb over the construction fence and then up to the roof, sitting there watching the ocean and drinking beer and playing jokes on the unsuspecting beach goers below. We had so many good laughs and so many crazy nights that I still smile just thinking about all the trouble we got into. The more we got to know each other, the more open we became with what was eating us up inside.

He told me about how he had watched as his best friend Nathan Windsor was shot and killed right in front of him while they were on patrol and how he wanted to get out and help but was stuck inside the Humvee as bullets and debris pinged against his door. He told me about how he learned that his bunkmate Blake Howie had been shot and killed on patrol while Clay was on base manning the radio and how he slept in the lower bunk after that, just to be closer to his friend. He told me about how he had been shot through the wrist while providing security for other Marines and how just seconds before the bullet cracked through his wrist, that’s where his head had been resting. He was sent back to the States early and always felt severely guilty that he didn’t finish out the deployment with his unit. He talked about Afghanistan and some of the good and bad times they had there. When the movie Restrepo came out, I went and saw the screening with him and we talked about how similar it had been to his deployment. In turn, I told him about Alex Arredondo and Nick Skinner who were close friends from my company and were shot and killed during the final days of our assault in Najaf, less than one day apart from each other. I told stories of their lives and smiled as I shared them with someone who could really understand the personalities and depth of character that each of these men had. I told him about the raids and the fighting and the cemetery which we had fought through. I told him about friends who had been injured and sent back early, just like him. I told him about the jokes we played and the pranks we used to pull on one another. I told him about a few of the ridiculous mistakes that I had made because I was such a young Marine and had no idea what I was doing. It was good to talk about all that stuff. Talking to Clay was far better than any VA counselor I had ever sat down with. Clay knew what it was like to fight and to lose friends and to be afraid and to wish that you could go back and change time. Clay knew the sights and sounds and smells and joys of war. He understood the humor in facing death every day and smiling back. He understood the bond that only those who have served together in war can ever know. I was able to open up so much bottled up stuff just because of his willingness and openness in talking to me.

Clay finally talked me into doing a veterans therapy bike ride with him from San Francisco to Los Angeles, with a group named Ride2Recovery. R2R had been created and developed to help heal the physical and mental wounds of combat by providing cycling opportunities. When Clay showed me the photos in his hallway of him pushing double amputees in a hand cycle and riding through the scenic coastline with other guys who had done the ride, I was in. I still didn’t think that I had any reason to do the ride as an injured veteran, since I had never been injured, but I wanted to be a part of the experience; so, I support raised the $3,500 that civilians were required to raise. Little did I know how much I was going to learn about what other vets had been doing to reshape their lives. When the ride began, I had never been on a road bike in my life and I had never used clip-in pedals. The first time I tried was in the parking lot of the hotel and I clipped in with both feet at the same time and fell over with the bike on top of me in front of an NBC news crew. That week we rode over 450 miles. As we rode, I had to rely on other veterans and talk with them so that I wouldn’t end up riding the whole day by myself. As I did, I learned a lot about them and a lot about myself. Stuff that I had only spoken to Clay about started to come out in snippets to other vets and it felt good. It felt as though with each person that I spoke to a small weight was lifted. I learned that PTSD wasn’t something to be ashamed of and denied, but rather it was something to be admitted and confronted. I learned that sometimes the visible wounds, such as amputations, are the easiest to heal but wounds like guilt, regret, anger, anxiety, depression, and sadness were more difficult. Clay and I were roommates during the ride and I tried to keep up with him as best as I could, but usually he was just too fast for me. I spent a lot of time riding with new people, pushing the hand cycles, and forging bonds with new friends that I still speak to today. During the evenings, we would have big dinners by the American Legion or VFW or some other group. There would be talks and applause and good times… but I noticed that Clay slipped away to be by himself every chance he got. At the big dinner night, he and I were at the same table, but I didn’t see him all night long. When I made it back to the hotel, he was there and had paid for a taxi back so that he could be alone. He was watching videos from his time in Afghanistan. I knew that Clay was having a really rough time making the readjustment to civilian life but this is when I started to worry.

Clay helping a fellow injured veteran during Ride2Recovery challenge

A short time after the ride, Clay and I spent more time together and the talks got more serious. They weren’t just war stories and mild depression anymore. We weren’t just hanging out and having beers for fun. He started to push me away some and used to tell me that if I hugged him he’d punch me in the face. I always loved to bearhug Clay because he acted like he hated it but I know he secretely appreciated it and he’d joke and say something like “I love ya too, ya jackwagon”. That seemed to have changed and I’m pretty certain his threat was serious, although I still hugged him anyway. We biked together less often and didn’t hang out quite as much. One day while sitting in his apartment in Santa Monica, he mentioned something about suicide and I told him that he should give his guns over to me until he was feeling better. He was on-board with the idea until I made a joke and told him that “maybe I’ll give them back”. I wish I wouldn’t have done that.

At some point around Decemnber or so, I would come home from school often to find him sitting on the couch in my bedroom, half a case of Coors Light cans scattered about his feet. I knew he was hurting bad, so I’d just have a beer and sit there in silence with him until he wanted to talk. On one of those afternoons when I had come home from school, he decided to call his mom while we were sitting there, which was a huge relief. We had been talking about how he felt and he had decided that maybe he would move back home to Texas to be closer to family. I don’t recall the exact conversation but I know it made me feel better that he was taking healthy action. I wanted to help him, but I had no idea how and all I could offer were some similar stories and shitty advice. He was further along in helping himself than I was and I had just started to sort through my own thornbush of problems, so it felt weird to try and give him advice about how to fix anything. I had no idea how to help. It was on one of these days that we were sitting outside, having a beer, that he started to cry and tell me about things that had hurt him in his life. Finally, I opened up to him about the biggest things that had haunted me. It felt good to finally get out the biggest things and have someone else know, but I’m not sure it solved anything… it just put it on the workbench as a to-do project. We talked about taking a cross-country roadtrip and writing a book. Shortly thereafter, Clay moved in to live with John Wordin, the director of Ride2Recovery. I thought it was great because it was a good stable environment for him, but I still missed having him around. From there he moved briefly to Colorado, then he went back to Haiti, then finally moved home to Texas (If I recall that sequence correctly).

Clay had had a lot of change in his life over the past few months. He had recently gotten divorced. He had to break the lease on his apartment and ended up owing money. He was in debt to the government for GI Bill money that had been paid to his university before he dropped out and went to Haiti to help with the disaster relief. The VA was taking forever to finish his disability claim paperwork and so therefore he had no real income. And now he was moving all across the country. I knew he must have been under tremendous stress. I’d still talk to Clay pretty often and he seemed to be doing well. I’d send him photos of the trails I was out biking. I was still worried, but I didn’t know what to make of the situation. We’d chat but the conversations were less frequent and not at all in-depth. He had just gotten a new job and I was proud of him. He had a new girlfriend and had just bought a brand new truck.

On March 31, I was asleep in bed because I worked graveyard shift, when my girlfriend came in and woke me up. She was crying and I hadn’t been expecting her over. I had no idea what was going on, so I asked her if she had gotten in an accident or something. She said something a couple times but I couldn’t understand her. She was sobbing and her face looked like someone had turned her heart upside down. Finally, she slowed down enough so that I could hear her “Hank killed himself”. I said “Oh my god, I’m so sorry”. Hank was her brother and had suffered a massive brain injury from skateboarding a few years earlier. She looked at me and said “What? No. CLAY. CLAY.” And I didn’t say anything at all. I don’t know what I was thinking or if I was thinking at all. She said “Dave, I’m so sorry”. And when it finally hit, I think that it may have been the saddest moment of my whole life. I don’t recall what I said but I know I was in some sort of shock for a minute or two before it hit me and I started crying uncontrollably. I tried to call off work but couldn’t even get words out when the lead officer answered the phone. I think that for the next couple of days, everything seemed to be thoughts about Clay’s life and I just couldn’t stop crying. It was so hard to believe that so many things would just never happen again. I had called Jake, Clay’s best friend, to see how he was doing and he mentioned that everyone was going to get together and fly to Texas for the funeral. I booked a flight for Lindsey and I and we went down to Houston. Over 1,000 people showed up and many more paid honors to Clay.

There are some things in this life that I will never understand. I don’t fully understand why Clay took his life and I never will. But, I do know this: Had I not met Clay, I probably never would have started doing so much of the therapy and other things that have helped me so greatly over the past several years. I may have never met many of the closest friends that I now have in my life. And God knows I would not have so many wonderful memories and experiences. I don’t know why certain things happen or what God’s ultimate plan is. But I do know that Clay Hunt’s life and legacy have been a testimony and an inspiration to countless other veterans and their families. Clay was one of the best men I have ever met. He exemplified the qualities of a Marine, of a brother, and of a friend. There are a lot of things I don’t understand; but I know that God has a purpose for each of us and that we don’t meet the most important people in our lives by accident or pure coincidence.

Rest easy Clay. I love you brother. I know you’re keeping an eye on the rest of us.

In Honor of Clay. Taken at our host house in India this month, 2014.