One of the things that has constantly impressed me throughout the World Race thus far has been the global nature of Christ’s church. As much as it might feel good to label Christianity as a “Western”, or even American religion—for labeling it as such allows us to think of it as a mere cultural item (think baseball or freedom fries) and thus relativize the beauty of its worldwide, worshipping body of saints—this simply isn’t the reality. The raw and heartfelt worship—through both music and lifestyle—of the churches, not only in Africa, but in the Eastern European and South Asian countries we’ve been to as well, is a far cry from McChristianity.

Simultaneously, believers chant in stately Eastern European cathedrals, sing in South-Asian house-churches, and dance on African dirt floors, feet stomping in time to the slow rhythm of the sheepskin drum, mimicking the intrinsic rhythm of God’s creation—the same creation that peers in through the church windows, as if the banana trees were offering their silent support for the worship of the God who created both them and the people inside.

In Revelation 7:9-12, the apostle John paints us an exciting picture of the time when these diverse worshippers will be gathered together, literally and geographically, to engage in concentrated, unhindered and eternal praise.

‘After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb. They were wearing white robes and were holding palm branches in their hands. And they cried out in a loud voice:

“Salvation belongs to our God,

who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb.”

All the angels were standing around the throne and around the elders and the four living creatures. They fell down on their faces before the throne and worshiped God, saying:

“Amen!

Praise and glory

and wisdom and thanks and honor and power and strength be to our God forever and ever.

Amen!”’

On this side of eternity, the picture is still beautiful, but it is separated geographically, somewhat hindered by the cares of this world, and many times watered-down. Nevertheless, when God grants me the opportunity of understanding some aspect of His global nature, it is a blessing.

God granted me that opportunity this Tuesday, as I was able to visit my Compassion International sponsor-child, Nshimiyimana Cyiza. Compassion International is a multi-national Christian organization whose aim is to “release children from poverty in Jesus’ name.” Through $38 or $45 per-month child-sponsorships and a number of other miscellaneous sponsorship opportunities (church leaders, widows, pregnant mothers), Compassion International has been incredibly effective in carrying out their mission. Throughout the whole world, Compassion sponsors 1.2 million children, and this number is growing rapidly.

Though I have been sponsoring Nshimiyimana, a five-year-old child from Rwanda, for almost two full years now, I never imagined that I would get the chance to see him in person. Sure, Compassion International does as good of a job of making the sponsorship feel personal as the typical many-thousand mile separation between sponsor and sponsor child will allow, by allowing (and encouraging!) handwritten correspondence, but even with those handwritten letters, Nshimiyimana was always, to me, a photo. The same thing has been true of the World Race as a whole, of course, in that my heart for the nations’ downtrodden had been set on fire when those downtrodden stopped being faces on a Red Cross television commercial and started wiping their sweaty faces on my khakis—but something was different about Nshimiyimana.

I think the difference may have been that I had known about and written to Nshimiyimana (Shim-ee-yuh-mah-nuh) before the World Race started. Because of this prior relationship, I really had a clearer point of comparison between “Nshimiyimana as concept” (as bad as that sounds) and “Nshimiyimana as person.” His name means “thank God.”

For the past few months, I had been e-mailing the Compassion International office back and forth, and it was definitely a bit of work, logistically speaking. When I view this work in light of the amazing act that it allowed to happen, however—connecting two specific individuals in a seven billion-person world—it was fairly little work.

Our Compassion International rep, John, a Kigali native, picked up Stephanie and I early Tuesday morning, because we knew it would be a long trip out to Ruramba, Nshimiyimana’s village in Southern Rwanda, just thirty minutes from the Burundi border. Over the three-hour drive, we watched the scenery change from urban to rural, as our black Jeep snaked through the lush Rwandan countryside.

Finally, we approached Ruramba. Tin-roofed mud houses lined both sides of the road and were grouped together communally, but with no apparent organization. Grids and right angles are something I haven’t seen, in housing layouts, since the States!

We arrived at the Ruramba student center soon after, and I recognized Nshimiyimana right away. He was shy—John told us I may, quite possibly, be the first Mzungu (“white person”) he’s even seen—but loving. He hugged me and I met his mother, Serena, as well. I think that I may have been more nervous than he was! Even though I knew that I was his only sponsor, I somehow felt as if I had to “live up to” or “compare with” other sponsors. This idea was unfounded, of course, but my mind can cook up some of the most outrageous scenarios when it’s nervous.

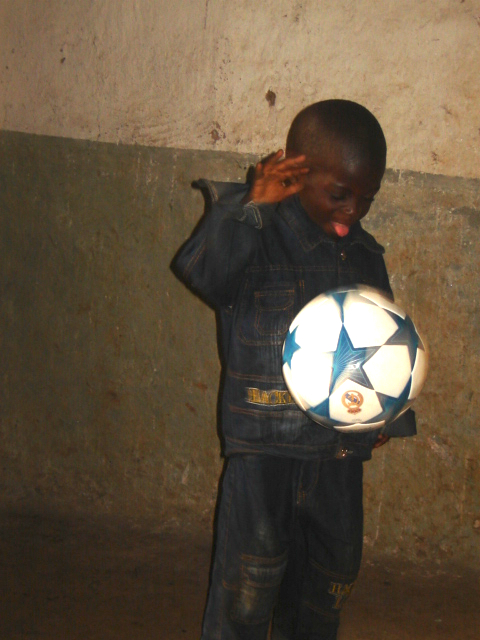

For the next hour, we ate bananas and talked about Nshimiyimana’s family and about what goes in in the Ruramba student center—that it was partnered with a local Methodist church and that Nshimiyimana, along with the other village children, were taught the Bible there every Saturday. And, of course, as is customary when two males meet, we talked (briefly) about football—soccer, in this case. Nshimiyimana plays, but not as often as he would like, as his makeshift soccer ball is made of plastic grocery bags, balled up tightly and taped together—something we’ve seen here in Kigali, as well.

After leaving the student center, we all piled back into the Jeep and drove to Nshimiyimana’s house. At his house, we met his brother, John The Baptist, and two of his sisters, Denise and Diane. We sat on small wooden benches, exchanged gifts (I gave him a soccer ball, a notebook, and a card, and his family gave me some tea that was grown in their village) and got to talk about school and duties around the home. The floor was dirt and the house was devoid of amenities—save a washing machine, and an old, dusty, radio—but the space was far from empty, as bodies both filled the room and peered through the open windows.

Nshimiyimana showed me his room and I was deeply convicted when I saw that the only possessions he had to his name were a few changes of clothes (some of which may have even been his brothers’), a shared bed, and a mosquito net. There was no electricity in the house, and thus no movies or video games. If Nshimiyimana and I were the same age, and I had come, from the United States, to visit him as a peer rather than as a sponsor, I have a feeling my jumpy brain would’ve gotten bored frighteningly quickly.

Before leaving, Serena showed us the family garden—an importance source of income—in the backyard. As I stepped over roots on the thin, brown, dirt path that led to the garden, and heard, through John’s translation, about the bananas, peas, and maize that the family grew, I felt as if I were a student being given insight into a world I knew very little of. The agricultural world was second nature to them.

Finally, a few hours later, it was time to leave and the trek home would be no shorter than the first leg of the journey had been. We took pictures, exchanged goodbyes, and, most importantly, prayed together. As we drove off and watched, through our thumb-printed window, Nshimiyimana, his family, and his neighborhood friends gradually fade from life-size beings to specks in the distance, I wondered whether I would ever see him again. The helpless romantic part of me assured the skeptical part of me that I would make it happen, but, either way, this visit was satisfying and impactful. The world’s children— Nshimiyimana, Laxmi and David from Nepal (Faint Hearts Don’t Win Fair Ladies), and precious Lluvia from Honduras (the poem I wrote about her is here at the bottom of the page)—have an almost mischievous way of lodging themselves deeply within my memory and refusing to leave.

As we drove home, Stephanie and I compared notes and praised, with mutual agreement, the creative power of God, as displayed by the beauty—the physical beauty—of Nshimiyimana and all his family members. As a Caucasian, I’m honestly not attracted to Africans in the same way as I’m attracted to other Caucasians—it’s just how I’m wired. In a different way, though, I can admire their beauty as they represent divine works of art, and this was so easy to with this family.

Their rich, brown skin worked as a backdrop for their beautiful eyes and convicting eyebrows. Each black eyebrow hair leaned tightly in unison with its partners, first up and then down, as if to say “this face means what it’s saying”. Long eyelashes fanned their faces, and, like the palm branches on the Jerusalem ground, covered their eyes, majestically, with every blink. Dimples served as landmarks, splashes of character among soft cheeks, equidistant between intelligent ears and modest lips; lips saddled with the task of sheepishly concealing teeth—impossible in a smile-friendly culture.

Recognizing the beauty of these people so different than myself helped me to appreciate the diversity inherent in the Kingdom of God. I think there is some part of our artistically-wired selves that thirst for majestic displays of diversity—like a peacock spreading its feathers. When we recognize that Christ’s kingdom is unimaginably diverse, we don’t have to create false and shallow diversity by slandering grace and tolerating heretical and unbiblical ideas.

For example, if our mental picture of Christianity is limited to a picture of white, upper-middle class Americans, then the part of our brains that can intuit, correctly, that “there is something else out there” will often bring home worldviews—worldviews that are not only logically inconsistent, but that spit on the cross of Christ—to serve as nothing more than hasty, un-thought out candidates to satisfy our unwritten, but desired “diversity quotient”.

Instead, when we recognize that faith in Christ Jesus grants us membership in a family that is diverse beyond our wildest dreams, we can easily accept the notion of worshipping, globally, one God, participating in one mission, and being enabled by one cross, because we understand that those saints who are doing so alongside us speak different languages and are from different places and different cultures.

I have yet to realize how my deep connection with one of these saints in specific—Nshimyimana—will affect my views on global brotherhood, but I do know that the impact will be vast. With the Internet and other modern advances in technology, ignorance and geographical distance are rapidly disappearing as legitimate excuses for me not to participate in God’s global work. My visit with Nshimyimana completely changed my answer to the question, “Who is my brother?” I have seven billion brothers.